Pictured above: Rill erosion in the lower Nyando River Basin, Kenya. Photo credit: Aida Bargués Tobella

For the Love of Restoration

The challenge of balancing quantity and quality in FLR efforts

By Aida Bargués Tobella, World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU)

FLR is on everyone’s lips. Governments all over the world have committed to restore hundreds of millions of hectares of degraded land, and the movement is just growing bigger. In 2011, the Bonn Challenge —a global effort to bring 150 M ha of degraded and deforested lands into restoration by 2020—was launched. Three years later, the original challenge target was endorsed and extended by the New York Declaration on Forests to bring an additional 200 M ha into restoration by 2030, making a total of 350 M ha, an area slightly greater than that of India or Argentina.

Regional initiatives that support and contribute to the Bonn Challenge have emerged around the world. These include AFR100 (the African Forest Landscape Restoration initiative), and the Initiative 20×20 for Latin America and the Caribbean. As of September 2018, 47 countries have made Bonn Challenge commitments, pledging to restore a total of 160.2 million hectares.

Underlying all these restoration initiatives is the Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR) approach. But, what is FLR, really? In a recent report launched by the Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration (GPFLR), FLR is defined as “the process that aims to regain ecological functionality and enhance human well-being in deforested or degraded landscapes. FLR in not an end in itself, but a means of regaining, improving and maintaining vital ecological and social functions, in the long- term leading to more resilient and sustainable landscapes.” The essence of the FLR concept is formulated by the following six principles:

The six principles of Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR). Adapted from Restoring forests and landscapes: the key to a sustainable future.

- Focus on landscapes: FLR takes place within and across entire landscapes, not individual sites, representing mosaics of interacting land uses and management practices under various tenure and governance systems. It is at this scale that ecological, social and economic priorities can be balanced.

- Engage stakeholders and support participatory governance: FLR actively engages stakeholders at different scales, including vulnerable groups, in planning and decision making regarding land-use, restoration goals and strategies, implementation methods, benefit sharing, monitoring and review processes.

- Restore multiple functions for multiple benefits: FLR interventions aim to restore multiple ecological, social and economic functions across a landscape and generate a range of ecosystem goods and services that benefit multiple stakeholder groups.

- Maintain and enhance natural ecosystems within landscapes: FLR does not lead to the conversion or destruction of natural forests or other ecosystems. It enhances the conservation, recovery, and sustainable management of forests and other ecosystems.

- Tailor to the local context using a variety of approaches: FLR uses a variety of approaches that are adapted to the local social, cultural, economic and ecological values, needs, and landscape history. It draws on latest science and best practice, and traditional and indigenous knowledge, and applies that information in the context of local capacities and existing or new governance structures.

- Manage adaptively for long-term resilience: FLR seeks to enhance the resilience of the landscape and its stakeholders over the medium and long-term. Restoration approaches should enhance species and genetic diversity and be adjusted over time to reflect changes in climate and other environmental conditions, knowledge, capacities, stakeholder needs, and societal values. As restoration progresses, information from monitoring activities, research, and stakeholder guidance should be integrated into management plans.

Momentum for restoration is clearly building. The quest to meet the ambitious global targets that have been set can keep this momentum up, which is great. But now that the time has come to move from commitments to action, we cannot continue focusing only on the number of hectares of land to bring into restoration. It is essential that we pay attention to the quality of restoration interventions and outcomes. This is, perhaps, one of the greatest challenges the FLR movement is now facing: how do we balance quantity and quality in FLR implementation efforts? How do we keep the momentum up while ensuring good quality restoration with outcomes that benefit both the environment and local people’s livelihoods, and that are sustainable in the long term?

The Global Landscapes Forum regional conference “Forest and Landscape Restoration in Africa: Prospects and Opportunities,” took place in Nairobi on the 29th and 30th of August and gathered actors from different sectors and backgrounds to discuss success stories and challenges in relation to FLR implementation across the continent. Building on the momentum of #GLFNairobi2018, WeForest, ICRAF and PARTNERS (People and Reforestation in the Tropics Network) teamed up to arrange a two-day event to discuss the need for a FLR quality framework in the African context. The event, which built on the experience gained from a previous dialogue held in Brazil in 2017 (see the brief from this meeting here), brought together scientists, decision-makers, practitioners and investors. Here are some of the key concepts that were discussed.

Some of the participants in the workshop “Forest and Landscape Restoration: Implementation for Quality. A dialogue on FLR Standards and applications to the African context.” Photo: World Agroforestry Centre/Martin Kavili

The need for a FLR operational framework

FLR is, by definition, a process. A long-term socioecological process that aims to regain ecological integrity and enhance human well-being in degraded landscapes. The six principles of FLR define the essence of this process, but as Robin Chazdon (PARTNERS) pointed out “We don’t have a clear vision on how to implement FLR or how to recognize it on the ground. There are no guidelines on how to translate the core principles of FLR into operational terms. Without this clarity, it’s not possible to ensure or measure quality.”

Along the same lines, Liz Ota (University of the Sunshine Coast) expressed her concerns about the fact that the vagueness of FLR could allow for outcomes that are below expectations – after all, large-scale restoration efforts have a spotted history. Nonetheless, according to Lars Laestadius (SLU), who led the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) work on FLR for many years, “The term FLR is vague on purpose. Nobody wanted to define it rigorously because this allows for flexibility.” But Laestadius also recognized that “the risk about being too flexible is that we end up deviating too much from the essence of FLR.”

What are the implications of deviating too much from the essence of FLR? Embodied in the principles of FLR is the adaptive management approach, an iterative process that involves the integration of design, management and monitoring to systematically test assumptions in order to adapt and learn. Adaptive management emphasizes the need to adapt to changing environmental and social contexts and to learn from doing. Thus, one may argue that, as long as an adaptive management approach is employed, it does not matter if the FLR process initially departs from the core FLR principles, as it has the potential to progressively improve over time, with guidance and support.

Yet, a FLR operational framework would ensure that the quality of the process at the outset meets certain basic standards or benchmarks, leaving room for further improvement but reducing risks of failure and fostering long-lasting transformation. In this sense, a key problem of not adhering to the essence of FLR could be that we end up having a series of short-lived projects, instead of driving transformational processes that are sustained over time. “A FLR framework that operationalized the kind of restoration that the FLR principles embody, would not only ensure quality outcomes, but also the long-term sustainability of these outcomes and the resilience of landscapes,” said Victoria Gutierrez, Chief Science Officer at We Forest. Michael Orangi, from the Rainforest Alliance, added that, “For us it is very key to attain sustainability. You might not get the chance to correct all your mistakes. You must have a basis.”

Current decision support tools are insufficient

Several tools have been developed to support different stakeholder groups in decision-making related to FLR activities. Some of these include:

- ROAM (Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology), a framework for countries to rapidly identify areas that present opportunities for FLR and to identify specific priority areas at national and sub-national level

- ROOT (Restoration Opportunities Optimization Tool), a tool that optimizes trade-offs among different ecosystem services to help decision-makers visualize where investments in restoration could be made that would optimize benefits for multiple landscape goals

- The landscape governance capacity framework to help stakeholders initiate and facilitate the process of landscape governance and bring it to a satisfying outcome;

- The Bonn Challenge Barometer of Progress, a tool designed to help pledgers track their progress on restoration as part of their Bonn Challenge commitments.

“These tools are useful for assessing FLR opportunities, financing, and priorities at national or subnational scales, but do not provide support for guiding implementation of FLR at the landscape scale, where local stakeholders must be empowered to lead and participate in interventions that will be sustained for generations,” highlighted Chazdon. For example, tools are needed to help guide the process to delimit the boundaries of a landscape where FLR will be initiated, and to develop a consensus vision and management plan of the landscape that effectively engages all stakeholder groups and mediates conflicts among them.

The Bonn Challenge Barometer of Progress tracks how FLR commitments are being achieved, but it focuses almost exclusively on the number of hectares brought into restoration, while less attention is given to the quality of FLR outcomes. How can we make sure that FLR activities have been effective? We need evidence that restoration has worked, that it improves people’s livelihoods. However, the only socio-economic indicator included in the barometer is the number of jobs created resulting from FLR activities. Moreover, clear monitoring methodology is lacking too.

ICRAF has developed a systematic biophysical monitoring framework for tracking indicators of ecosystem health over time. The Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF), has been implemented in over 40 countries over the past 15 years, hence enabling the largest field-based database on land and soil health indicators, hosted at ICRAF’s GeoScience Lab (GSL). Currently, the LDSF has been used to prioritize restoration in rangelands in Kenya and agricultural mosaic landscapes in East Africa, among other applications in South Africa and Tanzania.

Who could a FLR operational framework benefit?

An FLR operational framework could benefit a wide range of actors including implementers, investors, governments and private enterprise. One recent study argues that a framework could also help to market products from FLR landscapes, benefitting private enterprise and helping promote the upscaling of FLR.

For NGOs and other organizations involved in implementing FLR on the ground, operationalizing the FLR principles could be used to guide action to achieve the holistic FLR goals. “From our perspective, FLR principles are very useful but not when it comes to implementation. As an implementer I don’t really know if I am doing FLR or not. It would be very convenient to link the existing FLR principles to operational criteria which are, in turn, linked to a set of indicators that can be used to monitor and evaluate FLR outcomes,” said Gutierrez.

Governments could also benefit from such framework. According to Rafael Chaves, Secretariat for the Environment of the State of São Paulo, “Governments need an FLR framework to know whether we are achieving FLR or not. We don’t want FLR to be fake news.” Chaves also added that “Some people think it’s better to be vague about FLR, so that you are more flexible. However, if each of the governments that have committed to restore land is flexible in its own way, this will be a mess.”

An FLR operational framework could also be of interest to international restoration investors such as the World Bank, or the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) who provide financial support to implement FLR. Iretomiwa Olatunji, environmental specialist at the World Bank, noted that “People want to see a proof of the story, to see what you have achieved. We are looking at value for money, not money for spending, so we should be able to quantify the FLR outcomes. If an FLR framework is not there, and is not adopted by all countries, it is difficult to engage with the different countries and quantify FLR outcomes properly. We have a huge responsibility and something like this is critical.”

Do we need a “perfect plan” for FLR?

Many believe that too much analysis about the FLR process can lead to paralysis, as expressed by Tim Christophersen, Chair of the Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration, in a recent tweet in response to a blog post by Jaboury Gazoul which calls for a complex adaptive systems thinking approach in order to be able to scale-up existing scattered restoration initiatives.

When discussing about the need of a FLR operational framework, the same concerns are raised. Some people are reluctant to set any kind of FLR quality standards, as they believe that this would hinder the implementation of FLR by making the process overly inflexible and bureaucratic. “The more we insist in making FLR difficult to enter, the more rigorous conditions we put, the less people will want to do FLR” said Laestadius. But as Rhett Harrison, scientist at ICRAF and workshop co-organizer noted, “there is this tension between people not adopting FLR and having certain quality safeguards in place, we need a framework that is easy to adopt but that promotes better FLR practices and outcomes.”

A common, flexible FLR operational framework that embraces the inherent complexity of FLR

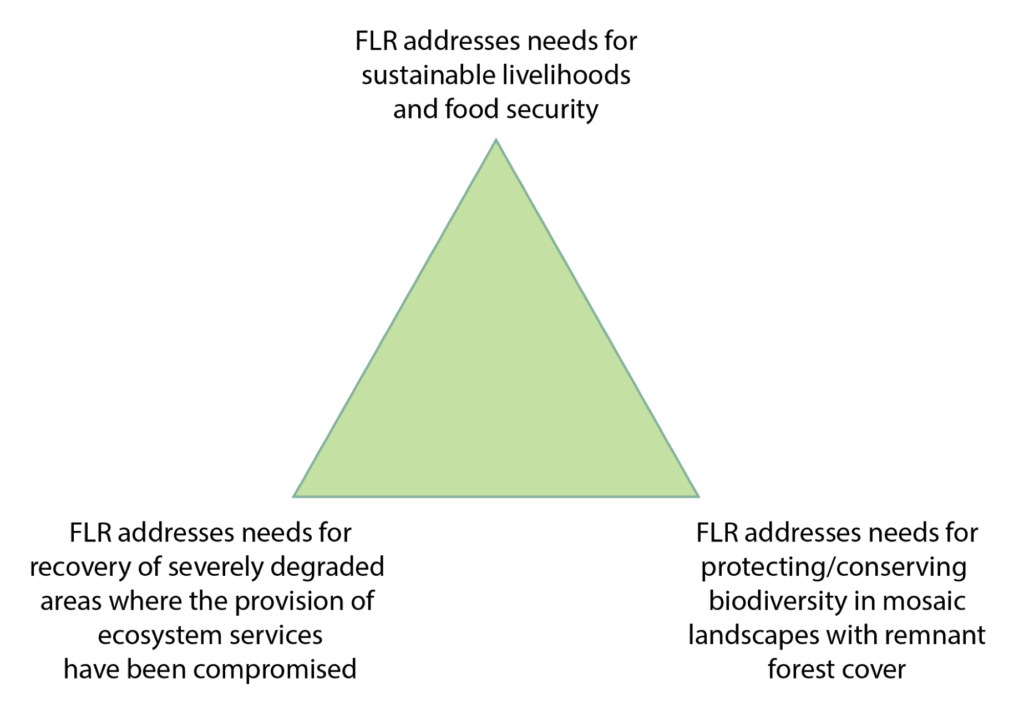

The FLR process is inherently complex, it is not only about planting trees or restoring forest ecosystems. “FLR can address different needs. How the various interventions of FLR are balanced will vary widely according to the context” stressed Chazdon, who illustrated this by means of a triangle:

“The visions of how landscapes could look like before and after FLR will vary a lot across these scenarios. In order to make the framework useful, this is a kind of complexity we need to build in,” added Chazdon.

A unifying FLR operational framework that embraces this complexity and that is flexible at the same time could be a very valuable tool. The framework could consist on a set of minimal benchmarks that should be fulfilled in order to meet the FLR principles, a common quality baseline. To describe this, Chazdon used an analogy we can all relate to: bathroom standards. “Bathroom standards are different around the world. Some bathrooms can be very sophisticated and have music and toilets with heated seats and a drier. Others might have a squat toilet. Some might have soap and towel paper and others might not. But there are some minimum requirements everyone agrees upon. Without such minimum bathroom standards we would have a lot of problems, such as contamination and disease. The core issue is that safeguards and quality are relevant and should be taken into consideration” she explained.

Governments have voluntarily committed to restoring land following the FLR approach. Thus, a FLR operational framework and related quality standards could and should not be enforced. They should not be seen exclusively as a reporting tool either. Instead, they could be used as a tool to know how to implement and conduct FLR, a tool for self-assessment and improvement. A tool For the Love of Restoration.