Many Secondary Forests Die Young in Southern Costa Rica

Reid JL, Fagan ME, Lucas J, Slaughter, J, and Zahawi RA. 2019. The ephemerality of secondary forests in southern Costa Rica. Conservation Letters 12:e12607. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12607

Looking out over southern Costa Rica from Cerro Paraguas, the landscape is a mosaic of farmlands and forests. Some of the forests are young and others are ancient – with giant trees hundreds of years old. Researchers and policy makers alike hope – and sometimes assume – that the young forests will eventually grow as big and complex as the ancient ones.

Does this actually happen? The answer will make a big difference for how much forests are able to contribute to species conservation and climate change mitigation. The reason that forest age is important (not just forest cover) is that as forests age they amass more carbon, more species habitat, more timber, and more of many other things that are valuable to humans. If forests are cut short by being turned into farms or infrastructure before they age, they will not provide these benefits in equal measure.

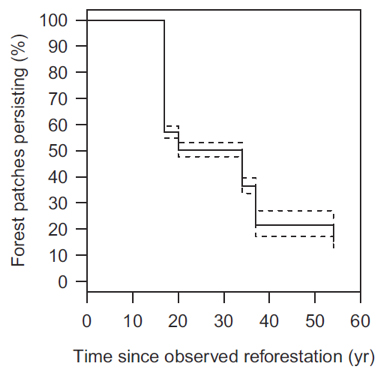

To find out how old forests get before they are converted to another land use, our research team analyzed maps of forest cover in southern Costa Rica from the 1940s through the 2010s. We looked for places where farms grew back into forest, and then we tracked those forests over time to see which ones lasted longer.

On average, we found that young forests persisted for only twenty years before being re-cleared. And 85% of young forests were re-cleared before they reached 54 years old. This is bad news for species conservation and climate change mitigation because many species take more than 100 years to come back to young forests, and it takes more than 80 years for a forest to become saturated with carbon. Young forests in other parts of Latin America are not doing better – in fact, forests in northeastern Costa Rica, eastern Peru, and central Brazil are being cleared even faster than the ones we studied.

The good news is that which forests persisted longer was predictable. For example, we found that forests along rivers persisted longer than forests that were far away from rivers. This could be because Costa Rica’s forest law prohibits clearing riverside forests or it could be because farmers want to leave forest to protect their water sources. This result suggests that Costa Rica could prioritize restoration of riparian areas to create longer-lasting forests.

A next step for this research would be to interview landowners and find out why they cut some forests while letting others grow older. We also want to study secondary forest persistence at larger spatial scales.

The PARTNERS connection

This project is a direct offshoot from conversations that we had at the first PARTNERS meeting in Storrs in 2014. It was a great coincidence that we started talking about forest persistence at the same time as Zak Zahawi and colleagues published a dataset that we could use to study it over a relatively large area at very fine spatial resolution. In addition to our open-access paper, we have also described this work in a blog, and through a video, and the work was also covered in Mongabay.

Secondary forest persistence in southern Costa Rica (1947-2014).

Coto Brus, Costa Rica: the region where we studied secondary forest persistence. (Photo by Leighton Reid)