Dialogues Between Scientists and Policy Makers to Develop a Shared Vision and Vocabulary for Forest and Landscape Restoration

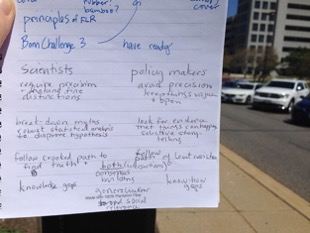

One rare occasions, late night discussions over wine can actually produce something that others find valuable. This happened in April 2016 when Lars Laestadius and I engaged in a lengthy dialogue about how scientists and policy makers differ strikingly in how they think and talk about forest and landscape restoration (FLR). Lars took the role of the policy maker and I took the role of the scientist. Fortunately, I took notes (see photo). A few months later, the editor of the American Journal of Botany invited me to write a guest article for their new section “On the Nature of Things”, and I was inspired to work with Lars to write this short paper.

We all agree on the premise that the FLR process should integrate the best available technical, traditional, and practical knowledge within a supportive political, social, and economic framework. So both scientists and policy makers need to be on board with practitioners and all need to work towards a common vision.

The challenge in communication and consensus building between scientists and policy makers emerges from the different societal roles they play and the different issues they face. Policy makers prefer to work with general concepts and vague definitions in order to facilitate communication and preserve options, whereas scientists use narrow and precisely defined concepts to eliminate ambiguity, ranking consistent precision over communication. Scientists want to distinguish “rehabilitation” from “restoration,” whereas policy makers are happy to call all interventions “regreening.” Policy makers look for evidence that helps them “sell” their policies, while scientists move forward by testing hypotheses through accumulation of evidence and use of robust statistics. Policy makers seek politically expedient solutions, whereas scientists follow a crooked path toward the “truth.”

In our paper, we emphasized the need to bridge the chasm between scientists and policy makers. We suggested that moving beyond their differences is necessary to develop a shared, feasible vision for implementing FLR. This goal requires that policy makers and scientists improve their understanding and respect of the legitimate needs of the “other” side and develop a common conceptual approach and vocabulary. We proposed identifying themes and contexts that can serve as focal points for dialogue among policy makers, farmers, landowners, and scientists (both social and natural). These dialogues need to happen both at national and subnational levels, so that enabling policies at multiple levels can be linked.

In our paper, we emphasized the need to bridge the chasm between scientists and policy makers. We suggested that moving beyond their differences is necessary to develop a shared, feasible vision for implementing FLR. This goal requires that policy makers and scientists improve their understanding and respect of the legitimate needs of the “other” side and develop a common conceptual approach and vocabulary. We proposed identifying themes and contexts that can serve as focal points for dialogue among policy makers, farmers, landowners, and scientists (both social and natural). These dialogues need to happen both at national and subnational levels, so that enabling policies at multiple levels can be linked.

Shortly after publication, our paper was critiqued by Veldman et al. (2016) who were dismayed that we failed to focus on the potential risks of forest restoration to native grasslands. We replied with a clarifying comment (Chazdon and Laestadius 2017), and emphasized that if scientists aim to communicate meaningfully with policy makers, accusatory statements and insistence on a rigid scientific point of view are not fruitful approaches.

The PARTNERS connection

This conversation first started in 2014, actually, beginning with our work together on “the definitions paper” that was inspired by the first PARTNERS workshop. Subsequent discussions about FLR were inspired by many issues that came up during 2015 and 2016, which revealed the chasm between science and policy, exacerbated by differences with concepts, language, vocabulary, and communication that impede the successful implementation of FLR. The conversation has now broadened to a much larger group that is discussing how to operationalize the FLR principles and catalyze landscape transformations all over the world.