Tropical Forest and People Research Centre, University of the Sunshine Coast

By Kanchana Wiset, Ph.D. candidate

Conservation and livelihood development are often viewed as trade-offs, but Forest and Landscape Restoration(FLR), attempts to reconcile them. Forest and Landscape Restoration is a long-term process that aims to regain ecological function and enhance human well-being in deforested and degraded landscapes. FLR has been widely recognized as a global restoration approach by many experts, conservationists and practitioners, through the Bonn Challenge, to bring 350 M ha into restoration by 2030. But how to practice FLR on the ground remains unclear. How can such a broad concept of FLR with such ambitious global restoration targets be brought into practice?

The Forest and Landscape Restoration Standard (FLoRES) Taskforce was formed to help guide practices and outcomes that adhere to the principles of FLR. The third FLoRes Workshop convened researchers, experts, practitioners to discuss how to best guide effective practice of FLR. The two-day workshop was held in Tacloban, Leyte Island, Philippines on 22-23 February 2019. There were 22 participants from 11 countries working in diverse organizations e.g. government agencies, NGOs, development agencies and academic. It was the third event of a series of workshop organized by the FLoRES taskforce to operationalize the principles of FLR in an effort to guide better implementation processes.

Learning first-hand about the central importance of community engagement

The workshop began with a field visit to Kawayanon community (Cabiran Balangay, Biliran Province) to learn how a pilot community-based restoration (CBR) initiative was implemented on the ground. In the past, the hilly areas of community were converted to grazing lands dominated by cogon grass (Imperata cylindrica), a highly flammable grass that impedes tree colonization. Deforestation has placed water supplies in jeopardy and increased the risk of dangerous landslides. The government invested in several past efforts on forest management for local livelihoods such as the Contract Reforestation Project (CRP) of the National Forestation Program, the Upland Development Program (UDP), the Community-Based Forest Management Program (CBFMP). Under the CBFM scheme, KFAI was formed as people’s organization (PO) in 2011, involving up to 100 members. However, the number of PO’s members sharply declined when government payments ended.

From 2013-2016, KFAI started a partnership with the ASEM/2010/050 Project of the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) focused on watershed rehabilitation. Through this partnership, the degraded lands in an area totaling 25 hectares were restored with a zoning system in place. Survival rates of trees were substantially increased because the PO’s members have been trained to manage quality seedling production and to maintain their trees plantation and protect them from fire. The partnership not only provided ecological and economic benefits, but also rejuvenated the people’s organization. Additional support to KFAI came from other agencies, such as CBFM-CARP programs (Agroforestry supports) and the National Greening Program. However, the group encountered some challenges in implementing their own watershed restoration project, such as managing their finances. Overcoming these challenges motivated the new ACIAR project, the ASEM/2016/103 project, Enhancing Livelihoods through Forest and Landscape Restoration to continue supporting Community-based Restoration in the Philippines.

Our visit to Biliran reaffirmed the importance of engaging local people in FLR and of viewing FLR implementation as a long-term process. FLR does not only focus on increasing tree plantation by local people, but also needs to ensure that local people are capacitated to manage the benefits of the restoration for their forestlands and livelihoods in the long-run. Through this visit, many questions were brought up with the group about how FLR should be implemented and can be optimized for an effective outcome. The experts also questioned how to scale up activities conducted within small management areas and how to determine landscape boundaries.

“FLR is a way to promote both livelihoods and reforestation, and it requires a guiding of practices on what types of interventions would be appropriate to improve both capacity and livelihoods at local level”, Prof. John Herbohn, Director of Tropical Forest and People Research Centre (TFAP), University of the Sunshine Coast (USC)

Challenges of transferring FLR from concept to practice

The second day of the workshop started in Tacloban city with a fruitful discussion on what is FLR and its concerns based on the perspectives of each participant. Many challenging issues of FLR were outlined as follows;

- A landscape boundary: How to define the landscape boundary and the areas to influence and be influenced by FLR.

- Scales and levels of implementation: How to determine the temporal and spatial scales for FLR implementation, and integrated the restoration efforts across all scales – national level to local level, to meet good quality standards.

“FLR is a local phenomenon that cannot use a regional perspective to make it happen”, Robin Chazdon, Professor, TFAP, USC

- Program-project-process: FLR is a long-term process, but it has been mostly implemented through program and project levels, which have a lifespan of implementation and may not be able to accommodate the long-term process of FLR.

- Cooperation and institutions for FLR: FLR requires multiple actions from different agencies but is often assigned as a task for forestry agencies. Which organizations should move FLR forward? How to institutionalize FLR and how to build synergies among relevant agencies?

“The problem of FLR is the ‘F’, but FLR is more than forestry and should not be only considered only within forestry sector” Patrick Durst, Consultant, Former Senior Forest Officer, FAO

- Interventions on the ground: FLR implementation must adapt to specific contexts on the ground. Although many countries have committed to the Bonn Challenge, there are still gaps of knowledge to guide implementation.

- Expected changes and outcomes: It is essential for FLR to make changes in land uses to meet ecological improvement and livelihood enhancement. Both aspects are important.

“FLR is not a goal but it is a way to make changes on how the lands have been used, by changing the attitude and behaviors of the users, and the changes should be measured and monitored”, Cesar Sabogal, Consultant, FAO

- Monitoring and evaluation: There is a need for a system to track changes along the way, and to guide how to monitor those changes and evaluate the outcomes.

- Funding: FLR has been driven by donors’ preferences. The funding must be used within a limited time period, as it is difficult for donors to fund a long-term process, because they need to see short-term outputs with less focus on how the process is going.

Are criteria and indicators needed to ensure effective of FLR implementation?

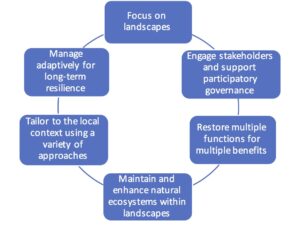

The result of the first discussion showed that it is important to have an operational framework to guide implementation of FLR on the ground. Where should this guidance come from? The FLoRES team proposed to start with the core principles that set FLR apart and that initially defined what FLR intends to accomplish from its origins around 20 years ago (Box 1). The participants worked to unpack the six core principles of FLR, recently endorsed by the Global Partnership on Forest Landscape Restoration (GPFLR).

The participants came up with two different approaches to identify the criteria linked to the FLR principles. One group of participants suggested that the criteria could be packaged within a broad conceptional approach, based on the FLR principles. Another group came up with an idea that many of the criteria are interlinked as processes that apply to more specific users and stakeholders and could be packaged as steps of an ongoing FLR process framework to ensure that the principles are being followed.

Common aspects were mentioned as the criteria or steps defining a FLR processes that are based on the principles:

- Defining a boundary of landscape from a comprehensive view integrating the ecological and socio-economic components

- Building a platform of stakeholders and institution setting for enhancing a cohesive decision-making and accommodating a negotiation of interests

- Setting long-term visions and clarifying of objectives to be achieved through FLR

- Having a baseline information and knowing a capacity of landscapes, in term of bio-physical, economic and social and cultural aspects

- Considering spatial planning for different land uses responding to different users

- Developing the options of restoration for both conservation and production including the management practices and interventions to be implemented

- Sustaining financial support including an analysis of markets, a development of business model, funding, and a benefit- sharing framework

- Establishing a monitoring and evaluation system for communicating the progress, sharing information and tracking the changes to guide for the adaptive actions along the process

Although workshop participants did not get to the task of identifying a set of FLR indicators at the workshop, the participants shared views on the characteristics of useful indicators. Indicators should be integrated across all principles and not be linear for each, because landscape continue to change, and people within landscapes change their needs and actions as well. A static framework for the indicator development is not suitable. Indicators should be able to track the changes at each level and show how they meet the outcomes of FLR. Theory of change could be fundamental for a development of indicators, and it helps to set up in which context that FLR should expect the changes at each level. Finally, the indicators should not be too complex, but should be usable and adoptable, be appropriate and friendly for people on the ground to apply.

Moving forward: the ‘Manila Declaration’ – a call for action

Many ideas came up as the alternative options for further steps to develop guidance frameworks for FLR on the ground. More and better communication on FLR practices is required. Especially, there is a need to compile a set of lessons learned and stories of on-the-ground implementation, which contribute to FLR implementation. The stories could provide the practical examples to convey how and what kind of implementation relates to FLR principles. Stories are an easy means of communication for conveying these messages to audiences in different formats such as videos, infographics, a success stories book, and detailed case studies. Providing examples would be more useful and powerful than a conceptional framework. Having only a set of criteria and many indicators is too abstract for implementation. Case studies can demonstrate how specific actions led to outcomes and how they illustrate specific criteria and indicators.

Funding FLR is a key point. How can FLR happen without funding support of donors? Some participants pointed out that some countries, such as the Philippines, have allocated substantial government funding to make FLR happen. There is a need to incentivize countries to adopt the FLR approach and to strengthen their capacity to foster implementation in a good way. Countries should therefore develop their own guidelines to fit with their contexts, by adapting from a more generalized set of criteria and indicators as a resource. Additionally, leadership is also a key mechanism to move FLR forward, including leadership at local to national level to encourage and facilitate FLR implementation.

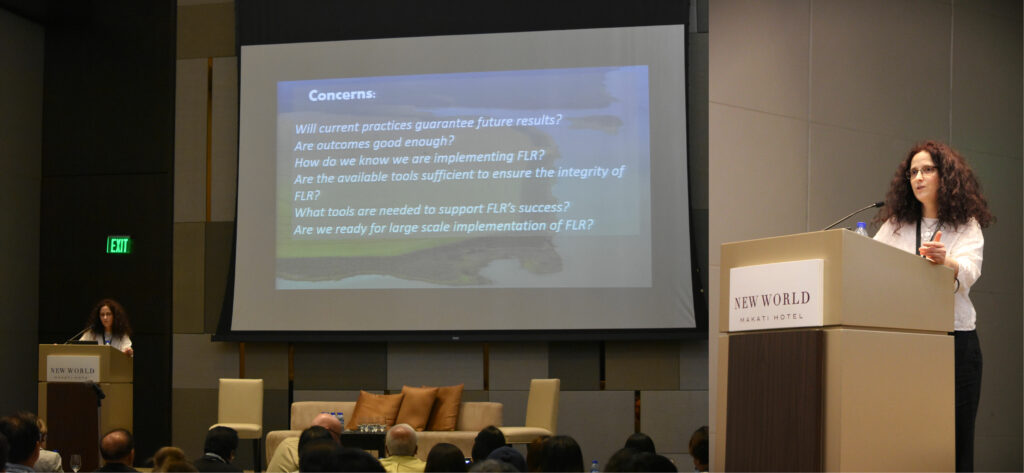

All of the ideas and opinions from this two-day workshop provided input for developing a declaration assembled by the FLoRES taskforce. This declaration was presented at the International Conference on Forest and Landscape Restoration: Making it Happen in Manila, Philippines on 25-27 February 2019. The ‘Manila Declaration’, presented by Victoria Gutierrez of WeForest, the coordinator of the taskforce, contains the key points regarding FLR implementation, challenges and concerns as well as calls for the actions to the interested parties. The key required actions include a development of a conceptual framework for guiding FLR in practice, providing case studies on how to operationalize FLR principles, testing of tailored working frameworks, engaging more collaboration in the taskforce, and advancing all actions through the international institutional platforms such as ICRAF, APF-net, and the GPFLR.

To make it happen on the ground, engaging local people in FLR is essential

The FLoRES workshop and the FLR conference focused heavily on efforts for guiding FLR practice. Broad concepts of FLR were discussed widely in both events, particularly, in terms of opportunities and challenges. Many research experiences with FLR were presented at the International Conference on FLR. Especially, many interesting case studies were shared, showing the outcomes of restoration efforts around the world e.g. Philippines, China, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Brazil, Peru, Ethiopia. All these cases required participation of local people at group and individual levels in different ways. Many strategies were applied to build good achievements benefiting nature and people. These accounts make a compelling case that engagement of local people is essential for making FLR happen on the ground.

Although we agree that local engagement in FLR is important, there is no specific guidance on what it should look like on the ground. For instance, it is still unclear how FLR cases are different from conventional reforestation interventions or community-based forest management. The key actions under the ‘Manila Declaration’ are aimed at filling knowledge and capacity gaps for FLR implementation. Cooperation of all relevant agencies is essential to ensure that FLR won’t get lost along the way.

Another gap is that most FLR studies published in peer-review journals focus on biophysical rather than social aspects. FLR case studies published by implementing organizations report on lessons and achievements of their projects and programs, but gloss over failures. Therefore, there is a need to consolidate and synthesize case studies and use them to help develop operational frameworks to guide FLR implementation, focusing on practical examples and outcomes that demonstrate operationalization of the FLR principles.

Finally, it is essential to understand the conditions and factors that influence the engagement of local people in FLR. These factors include local land uses, forest dependency of people, local needs, living conditions, socio-cultural systems and values, tenure and rights over resources, gender roles and interests, local capacity, local institutions, market drivers and economic opportunities within the landscape.

Specific social settings could enable or prevent engagement of local people in the FLR process. Principles of FLR require its implementation to tailor the process to the local context. Hence, it is a must for FLR practitioners, academic and extension officers to understand these contexts as a precursor for their implementation. These understandings provide the basis for developing the appropriate interventions to address the local contexts and engage local people effectively.

(kanchana.wiset@research.usc.edu.au)